Education in Burma and on the Border

The SPDC spends 25% of its budget on the military, and approximately 1.3% on education. Unsurprisingly, this has made Burma’s education the least effective in South-East Asia. Reliable, up to date statistics are hard to find, but a 2008 survey by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) found the following education statistics for Burma:

- 3 out of 10 primary school aged children are out of school.

- 70% of those who do start school are unable to finish at the primary level.

- 50% of students are unable to continue to secondary school.

All curricula and course material must be approved by the military. Universities have spent much of the past 20 years closed. The below-subsistence salaries earned by teachers result in teachers having to charge extra tuition fees to students, or take up second jobs. After graduating from high school, students are, in theory, able to enter higher education. Unfortunately, universities and colleges have only opened sporadically since student unrest in 1996 – the military is afraid of a repeat of the student-led democracy uprisings of 1988. There is no freedom of choice in higher education – students must take the subjects assigned by their matriculation marks, whether they have an interest in that subject or not.

All curricula and course material must be approved by the military. Universities have spent much of the past 20 years closed. The below-subsistence salaries earned by teachers result in teachers having to charge extra tuition fees to students, or take up second jobs. After graduating from high school, students are, in theory, able to enter higher education. Unfortunately, universities and colleges have only opened sporadically since student unrest in 1996 – the military is afraid of a repeat of the student-led democracy uprisings of 1988. There is no freedom of choice in higher education – students must take the subjects assigned by their matriculation marks, whether they have an interest in that subject or not.

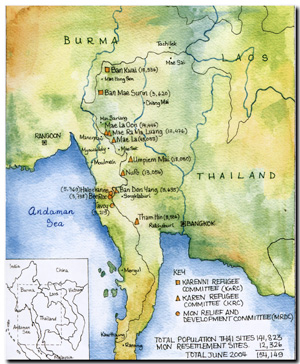

In border areas fighting often disrupts education, as students and teachers have to flee when troops approach. In Karen and Karenni refugee camps along the Thailand-Burma border, the situation is a little better. Local education departments and international NGOs have ensured regular teacher salaries, a more relevant and co-ordinated curricula, and teacher training opportunities. Consequently thousands of students from Karen and Karenni State come to the camps in search of schooling unavailable in their villages. However, refugee camps are less than ideal places to live and learn – insecurity generated by fear of repatriation into a war zone, crowded conditions and restrictions on movement outside the camps all take its toll on teachers and students. At the moment, many – especially the educated – are looking for resettlement opportunities in third countries. In the absence of a lasting political solution to Burma’s problems, this brain drain will continue.

As for the Shan, Mon, Rohingya, Pa-O, Chin, Arakanese, Kachin and Burman, exiles denied access to refugee camps, they survive as best they can as migrant workers in Thailand, Bangladesh, China and India. There are over 100 migrant schools set up to cater for this population; school roles range from a few students to over a thousand. These schools are funded, to varying degrees, by community organisations, religious groups, trade unions and Burma activists in exile. Most teach a version of the Burmese government curriculum, but some are aiming for the Thai government accreditation, so are working on coordinating their curricula with the Thailand.

As change comes to Burma, these exile groups – refugees, migrants and political activists – will need skills to help rebuild the country and achieve a lasting, sustainable peace. In the meantime, skills needed to bring about this change are the main priority.